posted on Saturday, July 31, 2021

With the onset of the U.S. Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) in 1986, millions of acres of farmland began being enrolled in the conservation program and the loss of U.S. croplands started accelerating. Furthermore, data indicate that while croplands in the U.S. and other high-income economies decrease, croplands of low- and middle-income economies have continued to increase since 1986. Crop-wise and country-wise empirical investigation of this trend show that the international market has responded to the U.S. idled acres by planting and harvesting more acres of the crops for which the U.S. has foregone production.

Table one shows the regression results reflecting the impact of the U.S. idled acres on competing countries’ harvested acreage of corn, cotton, sorghum, soybeans, and wheat.

Data indicate that an increase of U.S. idled acres – otherwise used for corn, sorghum, and soybean production – has a positive and statistically significant effect on Brazil’s harvested acres of these commodities. On an average, a one percent increase of the current 10 million acres of idled U.S. corn, soybean, and sorghum cropland would result in Brazil increasing its current 100 million crop acres of harvested corn, soybean, and sorghum by 0.375% in the subsequent year (see Table 1).

Data indicate that an increase of idled U.S. acres – otherwise used in cotton production – also has a positive and statistically significant effect on the total harvested acres of cotton in the following seven areas: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, the EU, the FSU, and South Africa. On an average, if U.S. idled cotton acres increases by one percent, these areas would be expected to increase harvested cotton acres from a combined 11.144 million acres to 11.175 million acres in the subsequent year – an increase of 0.27%. Looking at Argentina, the FSU, and Australia individually: Argentina would be expected to increase harvested cotton acres by 0.61%, from 995,833 acres to 1.001 million acres, in the subsequent year; the FSU would be expected to increase harvested cotton acres by 0.14%, from 5.296 million acres to 5.304 million acres, in the subsequent year; and Australia would be expected to increase harvested cotton acres by 0.27%, from 958,273 acres to 960,860 acres, in the subsequent year (see Table 1).

Data also indicate that an increase of idled U.S. acres – otherwise used in wheat production – also has a positive and statistically significant effect on the total harvested acres of cotton in Brazil and South Africa. On average, if U.S. idled wheat acres increases by one percent Brazil would be expected to increase harvested wheat acres by 0.41%, from 5.414 million acres to 5.436 million acres, in the subsequent year; South Africa would be expected to increase harvested wheat acres by 0.43%, from 1.268 million acres to 1.274 million acres, in the subsequent year (see Table 1).

Table 1. Regression Analysis of U.S. Idled Acres and International Harvested Acres.png)

Furthermore, these data indicate that in competitive international markets, acreage idling often creates an opportunity for competitors to take advantage of the foregone production of the country that idles otherwise productive cropland. Moreover, data also indicate this same behavior concerning shorter-term reductions of planted acres of the before-mentioned commodities (see Table 2).

Table 2. Regression Analysis of U.S. Planted Acres and Competing Country Planted Acres.png)

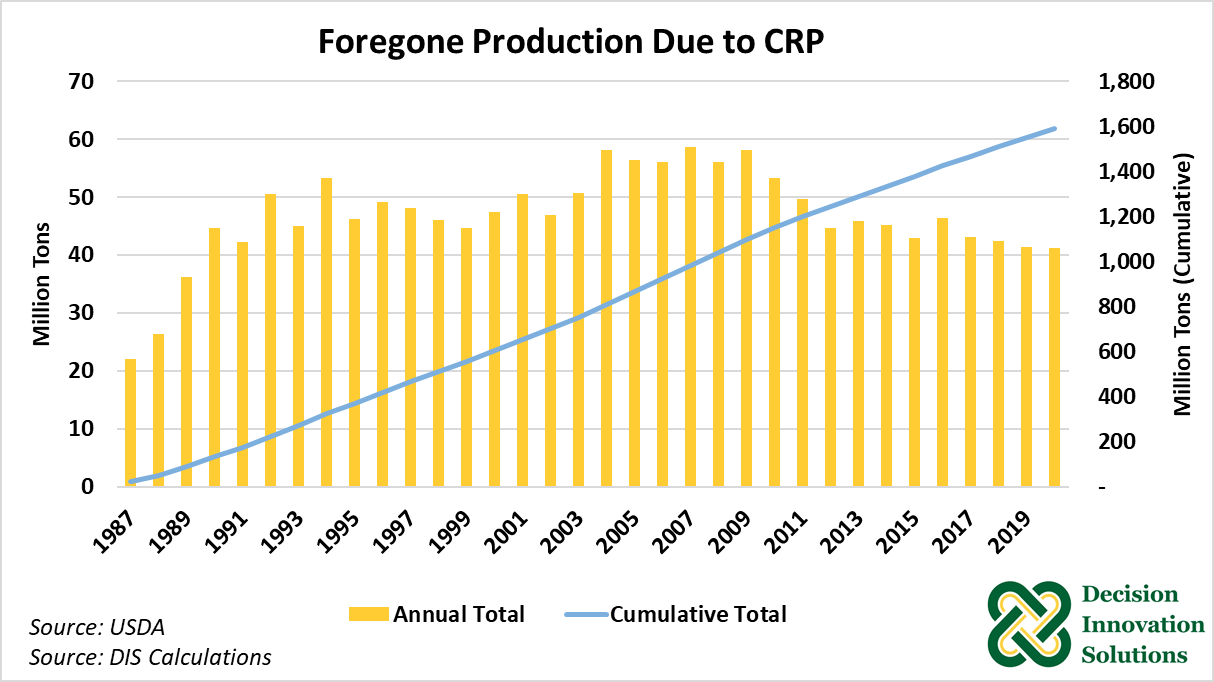

With the response of competing countries to idling U.S. croplands being to increase their harvested acres, and considering the intensity at which U.S. croplands have been idled under the CRP, total forgone production in the U.S. due to the CRP was calculated. The cumulative total forgone production of crops since 1986 – due to the CRP – is estimated to be about 1,600 million Tons (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Foregone Production in the U.S. Due to CRP

Figure 1. Foregone Production in the U.S. Due to CRP

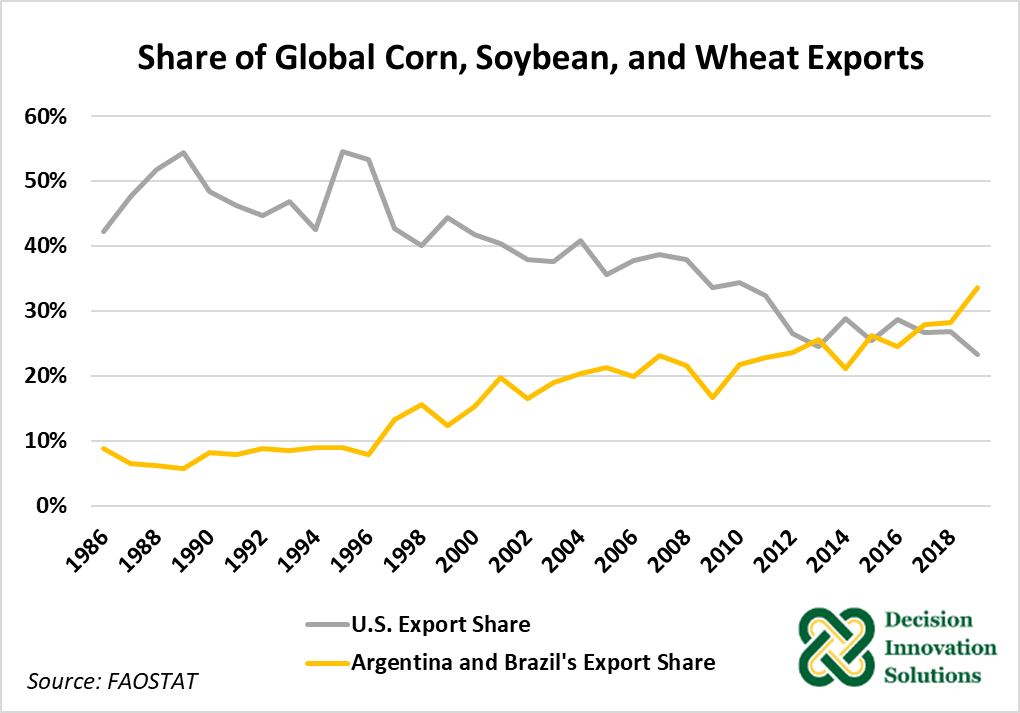

The idling of CRP land has several other consequences including international trade. The decline in the U.S. share of exports since 1986 is shown in Figure 2. Data indicate that the U.S. trade share has declined from about 45% in 1986 to about 23% in 2018. In contrast, Argentina and Brazil’s combined trade share has increased from about 10% in 1986 to about 33% in 2018 – surpassing the U.S. Therefore, due to idling CRP land the U.S. position in, and contribution to, the export market has been impacted. Furthermore, during this period the share of the revenue that could have come to the U.S. with the export of crops otherwise produced on this land was foregone.

Figure 2. Export Share of Corn, Soybean, and Wheat

Figure 2. Export Share of Corn, Soybean, and Wheat

Moreover, the growth in world populations and per capita food consumption has increased the overall demand for grains across the world (Mottaleb et. al. 2018). The U.S. is currently unable to meet the excess market demand due to compromised production caused by the idling of cropland across the country. Instead, the excess demand has primarily been met by competing countries and areas such as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China, the EU, the FSU, and South Africa. Many of these are developing countries with low infrastructure and/or low-quality pollution abatement technologies. Other such developing countries have also increased their production to meet the growing global food demand. To achieve higher production, these developing countries either cut down forests to increase cropland acreage, or they intensify production which often leads to the degradation of soil quality as many of these soils are more prone to erosion and loss of fertility. Deforestation, soil erosion, sedimentation, and the use of low-quality fuels and technology by these developing countries further lead to an increase in overall global pollution and environmental degradation.

The motivation to retire environmentally sensitive and highly erodible cropland from production is to restore soil quality and improve the overall environment. Higher-income developed countries, such as the U.S., are the proponents and active participants in government programs like the CRP which idles otherwise productive cropland to achieve this. However, it appears that the stalwart efforts of these developed countries are being counteracted by those of developing countries to meet the increasing global food demand.

References:

Mottaleb, Khondoker Abdul, Gideon Kruseman, and Olaf Erenstein. "Evolving food consumption patterns of rural and urban households in developing countries." British Food Journal (2018).